Isn’t it frustrating how the Baby Boomers, with their investment properties and multi-million dollar homes, are squeezing us out of the property market? Or, if it’s not them, then it’s the foreign investors snapping up houses they don’t even intend to live in!

“It’s not fair”, we lament, “I’ve studied hard, and I’ve been working since I was 18 – I deserve to be able to own my own home.”

Politicians nod in agreement, and there’s talk of policy changes, mentions of vague ‘sweeping reform’, although this seems unlikely as these decision makers are the very demographic keeping us out of the market (see aforementioned ‘Baby Boomers’).

And so on, and so on, and so on, you’ve heard the story. On every panel, in every paper, with every ‘expert’ being called upon, Australia is no longer facing a housing crisis, we’re living it.

And certainly, it’s not easy. Suggestions to simply “get a higher paying job” (cheers, Joe Hockey) or to “move out West [to rural Australia]”, as Barnaby recommends, really aren’t helpful. Nor is our Prime Minister’s suggestion that young people call on their parents to “shell out” in order to gather a deposit.

But there’s another demographic battling inflated rent prices and instability due to not owning their home: older Australians.

“WHAT?!” I hear you ask. “They’re the ones causing the problem!” And you’re right, in some cases.

But for a growing number of over 55s, the housing crisis is more than just a political annoyance, more than that devastating feeling of missing out at auction to someone older, wealthier, wiser.

Increasingly, for over 55s, it’s a matter of ill health, homelessness and – literally – struggling to survive.

So here are five ways that, in today’s housing market, it’s we the Millennials, who might actually be among the lucky ones (yes, you read that correctly).

1. If you’re looking to buy, you’re (relatively) financially stable.

Maybe you’ve got your deposit waiting to go (and if you’re in Sydney or Melbourne, realistically, this is likely going to be a figure of at least $30,000). Or maybe you’re merely starting to think about home ownership. You’ve got a well-paying job, perhaps a joint income with a partner… it makes sense to start thinking about buying.

However, while upsetting and irritating that it’s more and more difficult to get a foot in the door (pun intended), people our age looking to buy are financially stable. That’s what puts them in the enviable position that they can even think to buy. This isn’t the case for a lot of Australians, especially the 15,000 over 55s who are currently homeless, a number that continues to grow.

Many of these people – most of whom are women – have had stable jobs, but have ended up on their own (due to death or circumstance), and are now homeless. They’re living in shelters, on couches, in their cars. Similarly, older renters on the pension live in fear of staggering rental increases, forcing them out of their home. This is exacerbated when a partner dies, halving pension income, while rent and bills continue to get more expensive.

2. Superannuation. We have it.

Ah, superannuation. That necessary evil that glares at you every time you open your payslip – hundreds of your hard earned dollars directed into an account you possibly can’t even remember the name of, accumulating for you to enjoy upon your retirement.

Before 1970, superannuation wasn’t common. To receive it, you’d have likely been a high paid male in a corporate role. While it slowly became more common in the 1970s and 1980s, in 1988 only 34% of Australians had accumulated super.

In 1992, it became compulsory for employers to start paying superannuation. This means, for young Australians, we’ve been earning for our savings since the day we started working. Further, given super is invested, we’ve got four to five decades to see this money grow.

For older Australians (especially women), it’s common to have very little super and no savings at all. Often, women have spent their lives working for less – or for nothing, raising us children, caring for family members – and as a result, have very little super, and no savings.

3. We’re not invisible… in fact, we’re at the forefront of every ‘housing crisis’ argument.

This one might be hard to swallow, as it really can feel like our housing plight falls on deaf ears. But at least we’re at the forefront of the conversation. Do you think the government would tell anyone over 55 to ask for money from their parents to buy a house, to simply get a higher paying job, or to consider leaving their family and friends, and move out to rural Australia?

The vast majority of solutions being devised are for us to enter the market… not those at the other end. They’re not a part of the conversation at all.

4. By the time we retire, hopefully the experience of our elders will have created a better place to grow old.

One third of Australian pensioners live in poverty, with Australia being the second worst country in the OECD for financial security among our older population (second to South Korea).

Despite point number three, the conversation around housing affordability for older Australians is, fortunately, increasing. In a brilliant article in The Guardian last month, journalist Neives Murray said:

“In a country that prides itself on a ‘fair go’, perhaps we feel it’s unfair for a young hard-working couple, with lives full of hope and opportunity, to have slim chance at owning their own home. More unfair than the plight of a homeless pensioner who ‘had their chance at life’ and should play the cards they’ve been dealt.”

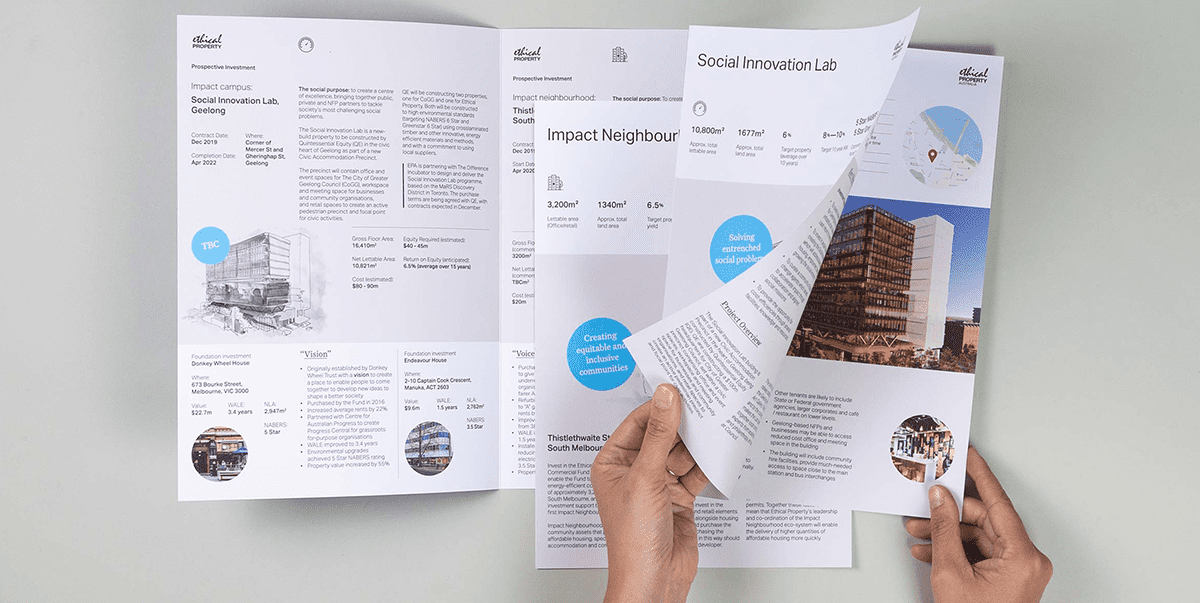

Further, there were several insightful segments on ABC Radio National in late March, examining not just the problem, but what the solution might be: from co-design projects, to affordable retirement villages, to changes to the pension. Perhaps if we make enough noise, in 40+ years when we retire, ageing in Australia will be blissful – we’ll be listened to, valued members of our communities. But that is not the reality for hundreds of thousands of Australians today. Instead, for them, it’s a daily struggle.

5. Rental reform will take the pressure off buying.

The precarious nature of the nation’s rental market is a problem felt by all renters. From bans on pets, to six-month leases, and random – sometimes huge – rental increases, the power real estate agents and landlords have over the lives of renters adds fuel to the ‘housing crisis’ fire.

And while I hope that every young hopeful homebuyer reading this is able to get into the market, for those of us who give up (and believe me, I’m close), rental reforms are on the horizon. It appears more likely that, in Victoria, longer leases will become the norm, pets will be allowed, and renters in future will be treated more equitably.

*This is the first in a two part series about the problems being faced by older Australians in the property market. Next month, we’ll examine the potential solutions.