“We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

— Winston Churchill

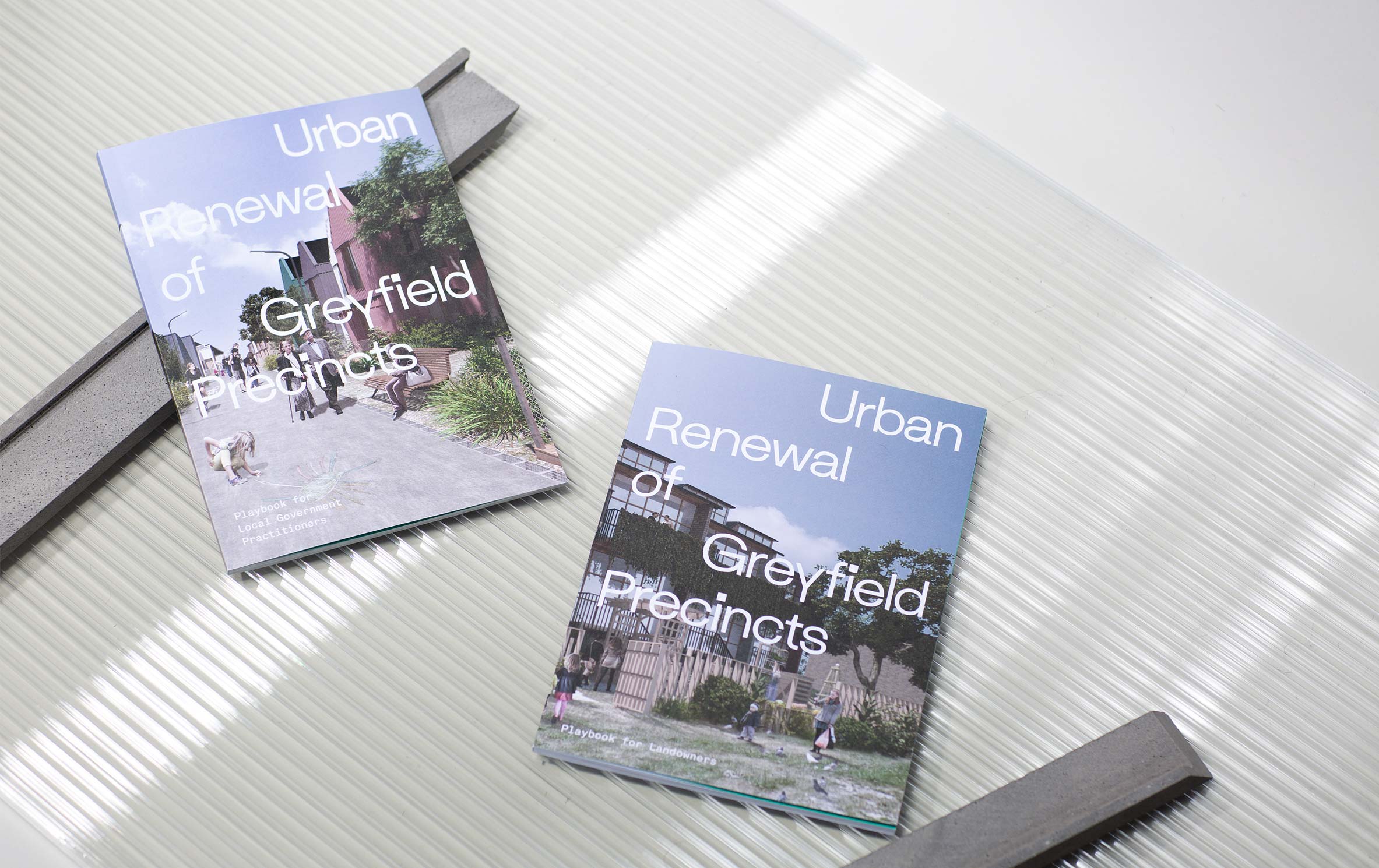

Ellis Jones has a practice focused on the opportunities created at the intersection of property, place and social impact. Over recent months we have delivered a number of projects, and entered discussions with varied ‘actors’ in the sector. From government and regulators (like the ARBV), to planners and researchers (Maroondah City Council / Swinburne), impact investors, developers and the design media.

The narratives are rich and varied, however it is clear that wellness and quality of life are clear focuses for those who wish to lead through policy, planning or product. Our 21st-century lives will be expressed through increasingly urbanised, high-density environments.

As users of architecture and buildings, we can, and must demand more from the built environment: its impact from the personal to the universal is all-pervading. Let’s shape our surrounds for good.

We innately shape our surrounds to influence and imitate us.

The majority of us will never develop an apartment building, design an office tower, or plan a suburb scale subdivision.

Many of us won’t commission architecture or build a house from the ground up.

But most of us will buy the odd pot plant, rearrange the furniture, mow the lawns, peruse the paint chips on a Bunnings pilgrimage for that perfect colour. Surely we all enjoy the deep sigh of relief sitting down to a freshly tidied desk.

In these small ways, we acknowledge the impact that our surrounds have on our experience of daily life. Our spaces are a vehicle for expression and aspiration: be that individual, or collective.

They say an owner inevitably resembles their pet, perhaps the same is true of their homes? The autobiographical nature of domestic spaces is one of enormous import in the realm of design for ageing and care. It’s a thread we reflect on in these notes from the ACSA Summit 2017.

These behaviours are so ingrained as to be subconscious and, yet, so often the desire to shape the backdrop to our lives ends at the front gate. The engagement starts and ends ‘at home’.

We are all consumers of architecture and design.

Often architecture and design are seen as something out of reach. Something for those with the means to commission it. However this type of engagement represents such a small sample of the means and modes that we all interact with architecture and design.

If you live in a multi-residential apartment, if you work in an office, you use architecture. If you walk to the shops, catch the tram to work, drive out of town on a weekend, you use design and planning of the public realm.

Brian Reed said, “Everything is designed. Few things are designed well”.

We all have a vested interest in best practice, to demand rigour and foresight in the creation of our environments, as they so innately impact our experience of the world, and expression of the self.

Zooming out: designing the urban fabric for wellness and productivity.

In the public realm, governments are exploring ways to better position the human and societal outcomes (happiness, wellness, sustainability, quality of life) at the heart of policy and legislation. Peak bodies like the Property Council are advocating new best practices. Leading developers are embracing quality of life, community integration and affordability as key differentiators in a crowded market.

A few of the key trends we have noticed are below:

Connected, local and productive lives.

The realities of work and life in the high-density urban future will be intimately connected. No longer is work the domain of the office, and life the domain of the home. Boundaries are fluid, and our spaces must be flexible to accommodate this. Living and working within a local, connected community creates efficiencies and promotes personal productivity. Greater affordability and innovative pathways to ownership help make this a reality.

Wellbeing, well building.

New government guidelines promote individual and corporate wellbeing, by better design. At a base level, this can be accessibility, sustainability and environmental impact of process and materials. That said, organisations are investing beyond the baseline as data continues to indicate that a ‘well building’ fosters a happier and more productive workforce. Circadian lighting systems, air filtration and EMR shielding are becoming increasingly commonplace, as too is designing for the needs of a diverse workforce (led by OTs, human factors, ergonomics and behavioural psychology experts).

Planning for impact, selling with purpose.

Planners continue to sharpen the focus on fostering cohesive and engaged communities, high quality, sustainable housing stock, biodiversity and green space.

Developers are beginning to realise that there is opportunity for efficiencies and product differentiation on offer if they are willing to fully embrace the planning, measuring and reporting of their social impact. In so much as their developments are:

- better aligned with public policy, reducing regulatory issues or planning delays

- better integrated with local communities, reducing appeals or complaints and building a community of potential buyers

- better differentiated: sales and marketing narratives are driven from authentic community engagement and best practice in architecture, design and amenity, rather than manufactured based on an image of ‘lifestyle’. The promise is lived through the fabric of the development.

You could do better.

We all could. Each of us, as consumers of design and architecture, has the opportunity to actively consider our environments; to claim agency in the spaces that hold our life and work.

For those leaders in public and private realms who shape the very fabric of our cities, the challenge is clear, and the opportunity for mutual benefit evident. Let’s authentically create buildings and places that foster quality of life, embrace principles of sustainability, generate greater productivity, and take us positively into the urban future.