A big thank you to the Melbourne Centre for Behaviour Change Conference for another fascinating day among fellow travellers.

This annual event continues to strike the perfect balance between knowledge exchange and collegiality.

Like seeing an arts performance, it’s always beneficial to sit with what you have experienced and register what stayed with you. This group of takeaways is therefore absolutely subjective.

In a program packed with insights and the odd epiphany, these are the four themes that found their way from the frontal lobes to the hippocampus – hopefully a little bit quicker and richer than Homerus Simpson’s (who, we were reminded, possibly represents more basic and counter productive subconscious responses than we like to admit).

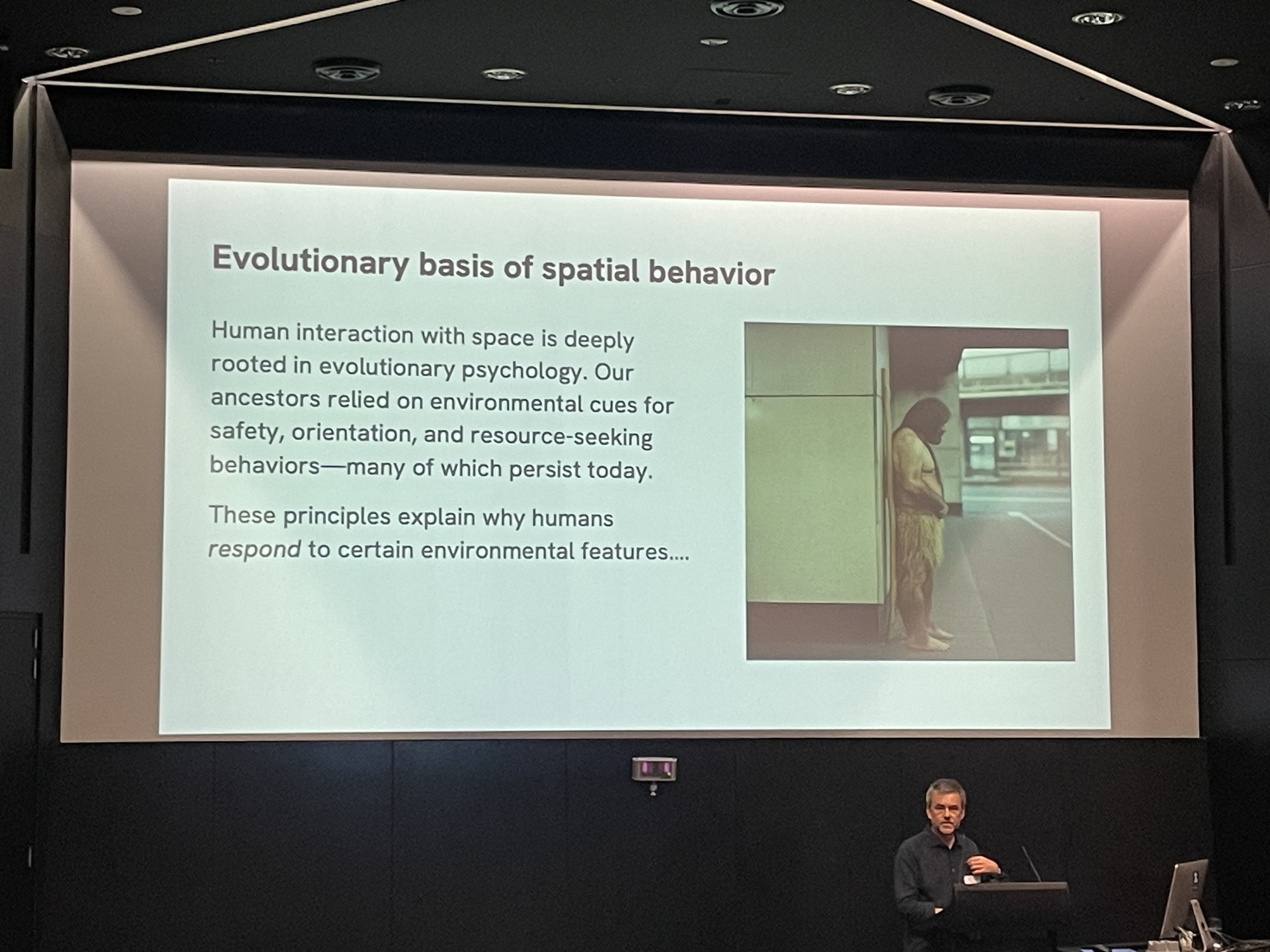

The Built Environment – urban planning is a very nice playground for behaviour change.

Ever since IDEO took off from where Edward De Bono finished, we’ve been using ‘design thinking’ to make human centred experiences.

But before then, was Gibson’s Affordance Theory. Published in 1979, it is as relevant now as it was when Boogie Wonderland was topping the charts.

‘An affordance is a relationship between two (or more) interacting systems that describes a potential behaviour that neither system can exhibit along.’

The theory views cities as layered affordance systems. There are four layers:

- movement (walking, cycling, driving)

- social (gathering, lingering)

- economic (trading)

- environmental (shade, air quality)

At the foundation of affordance theory is the premise that public space influences how we navigate a place – and think about ourselves. That is, the design of a place guides the behaviour of people using it, with identity, belonging, health and wellbeing, and many other benefits.

Prof Dirk Van Rooy shared an example of how transforming a central street in Antwerp, previously dominated by cars and delivery vans, also transformed the experience of city residents and visitors. To achieve the ‘affordance shift’ they:

- Made walking and cycling the default option.

- Included green space to promote a biophilic connection (subconsciously we all love nature).

- Established ‘implicit affordances’: replacing signage with other visual and felt cues, such as pavement texture differences to infer bike, pedestrian or shared lanes so people moderated their own speed and safety.

- Mapped ‘desire paths’, anticipating likely ‘natural’ movements of people rather than retaining or constructing paths that were frustrating or ignored. If you’ve been to a local park and seen how new paths appear across grassy areas because people want to ride or walk in a direction the constructed paths don’t, that’s a desire path.

- Created opportunities for ‘environmental feedback’. For example, placing more seating, which promotes lingering and socialising, and is therefore regularly occupied by people, and leads to more and more people using it. These are ‘sticky points’. Kind of like a restaurant with people in it, versus one that’s empty. Most of us choose the busy restaurant.

- Designed ‘sequential unfolding’, using form to guide space use: commuting versus lingering, retail versus socialising; examples are sidewalk widening and using line of sight to infer thoroughfares versus sheltered nooks.

On that last point, have you ever found yourself walking closer to a wall or guardrail? That’s likely ‘thigmotaxis’, or wall following behaviour. It makes us feel safe in unfamiliar spaces.

Now, if you have worked for a local council, you’re probably thinking these concepts will only fuel the fear traders have of economic collapse from removing street parking or, horror!, replacing roads with bike lanes.

Well, in the Antwerp example, there was an average 10% increase in business transactions. Bank the $$$.

A key point made by Prof Van Rooy is that good affordances don’t force, they invite.

So, don’t ban cars, make their use feel unnatural or not socially acceptable.

We love it when design thinking meets social identity and behavioural science.

Allegory and community led research.

Prof Cathy Vaughan shared her work applying behavioural science to build the capability of Vietnamese women to address tech-facilitated violence, and Aboriginal communities to reduce the prevalence of STIs.

Ellis Jones is working with Gippsland Women’s Health on a behaviour change campaign to address technology facilitated coercive control in regional Victoria. And we recently scoped a project to support community coalitions in Queensland Aboriginal communities design nudges (building on this work over a decade ago). So, Prof Vaughan’s work is highly relevant.

For well over two decades, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have been endemic and persistent in many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, especially in regional and remote areas win Australia. In 2023, when compared with Australian population averages:

- Infectious syphilis is five times higher and congenital syphilis cases are 21 times higher;

- Chlamydia is nearly twice as high; and

- Gonorrhoea is more than four times higher

A striking image showed First Nations community members articulating concepts in a culturally relevant way: visual communication. Drawing and making them.

It was a good example of a decolonised process, by community for community. As our friends working in Population Health at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute would say, to help, behavioural scientists have to ask: What are the priorities of the community? How does the community want to do the work? Research and design respond to the answers.

Only Aboriginal people understand the socio-cultural context and codes in their own communities, within which behaviours need to change. And this can be very different even in neighbouring communities.

The image evoked the way Nelson Mandela used animal avatars to explain the changes in South Africa to a population that had never been involved in charting their own destiny, and now needed to come together to remake their nation after apartheid.

And… it recalled Lego Serious Play. Which was a thing. But that’s another blog article.

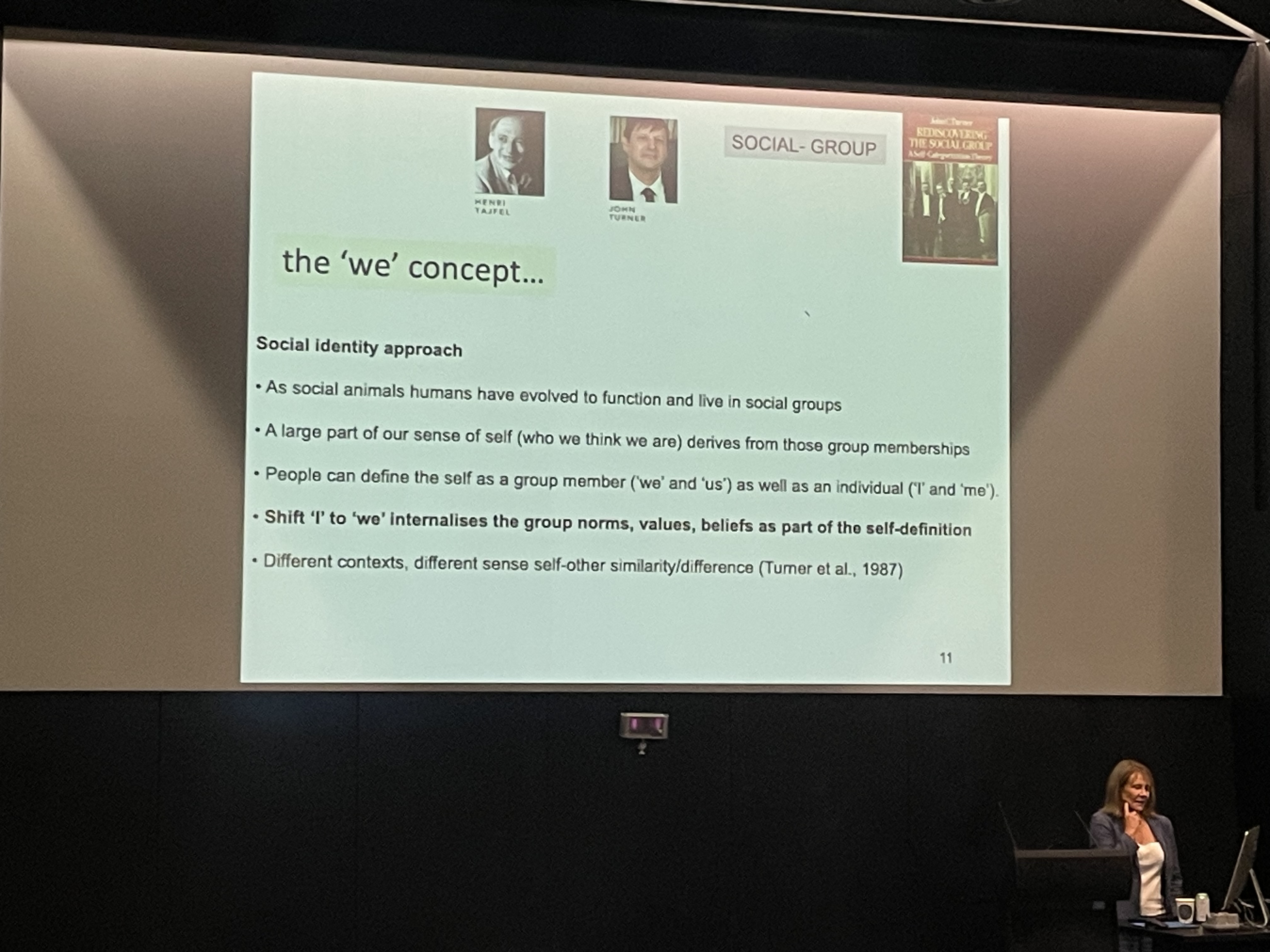

The concept of We.

Prof Kate Reynolds’ presentation was a call to arms to boost the focus on social identity and group psychology in behaviour change approaches.

Rattling through many well known frameworks, she demonstrated its absence.

It is much easier to change a group’s behaviour rather than an individual’s, and too many models focus on individual psychology.

Ellis Jones has been heroing identity in behaviour change for many years. It features as a domain in the Pivot Playbook because we know from our work the importance of not only social identity but also place identity in driving behaviours.

We want to belong. We value the opinions of our ‘in group’, even if they change. We don’t even countenance the opinions of ‘out groups’. It’s a fact at the heart of identity politics.

So, more work to come on applying the ‘concept of we’.

PR value versus P value.

The importance of influencing people in power – whether funders, policy makers, or leaders in different fields – was returned to several times across different sessions.

It was refreshing when, at one point the debate went to taxonomy – ‘manipulation sounds too nasty, persuasion is nicer’ – and an audience member stated confidently that manipulation, influence and persuasion are core skills of people in power: they understand it, value it, so do it.

The vital ability to influence and communicate are validated in the philosophy of science. It’s why bad theories stick and good theories sink.

Creativity theory incorporates influencing skills as important to creative process and outcomes. If you can’t generate interest, you can’t get funding, you can’t keep people on the bus long enough to get results; and, when you do achieve something valuable, you still have to sell it to sceptics and overcome vested interest in the status quo.

An audience member put it as ‘PR value versus P value’. One for the statisticians!

In Ellis Jones’ work we always recommend that evidence be accompanied by storytelling. Case studies are more arresting than data. Particularly if they are in the electorate of a government minister with their hands on the purse strings.

That’s a crude summary of our Melbourne Centre for Behaviour Change Conference. Hope to see you next year.