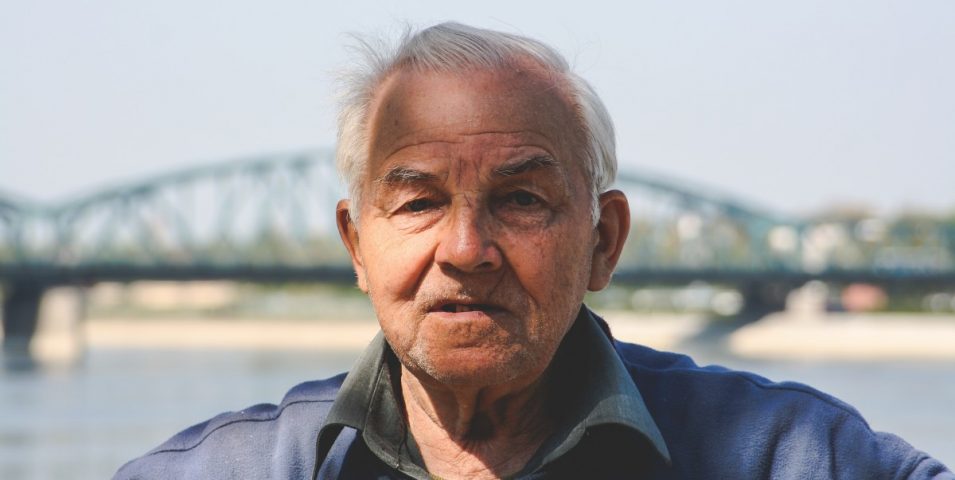

Sue Hendy, Australian director on the International Federation on Ageing board, shares her experience of aged care – as a consumer advocate over many years and, more recently, as daughter of a nursing home resident.

The Royal Commission in Aged Care Quality and Safety has brought the realities of aged care, and particularly residential care, out from behind the picket fence and the security door, into mainstream public consciousness.

For those working in the sector it has sharpened our attention to questions of care and rights and how these can be balanced, to provide the right level of care expected and required, within existing financial and other resource constraints.

In this article, part of our series on the royal commission, we take the older Australian (the ‘customer’) perspective.

Walk in my shoes.

As we age and we acquire a disability or illness, we may require assistance to carry out our daily tasks. As this illness or disability advances, the level of care required may be provided in a residential care facility. Our expectation is that our individual needs will be met, care provided, and we will be treated well, medical conditions managed, and we will see our days out in comfort.

United by laughter lines and long memories, older Australians are otherwise a deceptively diverse population group with increasingly complex physical and mental health conditions. Yet they have some common needs that shouldn’t feel unusual to anyone younger: to be treated with respect, to have one’s dignity maintained (the opposite being humiliation); to have basic needs for warmth, food and shelter tended-to. Most of all, to have continuity of culture, community connections, and simple pleasures – to be able to do the things, maintain the traits and lifelong passions, that make every person unique.

Let’s delve deeper. ‘Respect’ is responding to individuals in a way that their self is acknowledged, and their autonomy or self-law is enabled as much as possible. If someone has dementia, this can be difficult; but, by understanding the capacity, likes and dislikes of an individual, we can make a good go of it.

Respect also means being listened-to, responded-to, with empathy and compassion. Which leads us to…

Who provides care?

If you’ve walked the corridor of a contemporary aged care home, you can’t miss the gentle and confident motion in which the best carers guide residents. One arm bent, supporting that of the older person, a safe and welcome intimacy.

The career path of people working in residential care is a limited one, with the pay being low and the training required often inadequate. This, in turn, can lead to several outcomes we are now hearing about in the royal commission.

The system relies on ‘new Australians’, people recently arrived from overseas, to take up these roles.

This training does not equip them adequately for the job they are required to do. This is not hospitality or office cleaning, although these are both worthy pursuits when establishing a life in a new country. The responsibility and the emotional resilience required of carers is extreme by comparison.

Older bodies are very sensitive and have poor tolerance levels for medical problems, requiring good levels of nursing skill, even at an oversight level, to ensure they remain well. People experiencing mental health issues leads to behaviour that can seem strange and be hard to manage if a carer is not experienced and highly trained.

This can result in bewildered or overwrought staff responding inappropriately, speaking loudly and using physical force, intensifying the older persons fears and behaviours.

For many, care is a vocation and a talent. These are amazing people who create the best end of life experiences in difficult settings; who work with families, supporting them in their journey. And they do this in simultaneous and non-concurrent cycles of around two years, the time a resident will spend in this, their last home.

Perceptions & expectations.

If aged care homes are places that such humanity and care is expressed, why does the sector have such a bad rap?

If you walk down any high street and ask people about the residential aged care sector, most will react saying they don’t want to ‘end up there’. Does it mean they believe the care is inadequate or the home dangerous? Or is it simply that it represents ‘the end’ and, until we get there, we’re all certain we’ll pop off in our sleep somewhere in our late 80s or early 90s? Is it that most Australians haven’t been in an aged care home, so their perceptions are shaped by negative media reports? Is it that dementia is confronting when you don’t have the education to understand it?

People are living longer and, as a result, managing the deterioration in their health for many years. Being ‘old’ is becoming much more ‘normal’ yet Australians seem to resist it more, not less. If we embraced ageing and age, we might not fear it so much. Then the restful places in which we choose to end our days might be welcome settings for enjoying the last of life, and saying goodbye.

Ellis Jones has developed a model to support the sector to proactively address and respond to the Royal Commission. Beyond the initial submissions, our approach focuses on engaging older Australians and their families into the future. And responding tactical over time to strengthen, not weaken, the sector’s resilience and integrity. Download the model here.