Any psychologist will tell you that almost all human behaviour is learned. The business academic will relate that specialisation leads to economies of scale, hence the emergence of huge, highly organised businesses over the past couple of centuries.

These two factors, and others, see us focus our learning and critical thinking into models and methods of practice. We refine how we perform tasks, getting more efficient and competent over time.

We watch our colleagues, absorbing not only their practices, but their attitudes and characteristics. And we see opportunities that fit within our professional frame.

I have noticed how a social entrepreneur often does not understand the commercial reality and timeframes of business and thus fails to sell his/her idea, regardless of its promise. I have seen consultants step into this breach, able to connect the large and small, the considered and the impassioned. But consultants have the most finely honed practices of all, and find it hard to work or see opportunity outside them.

It is fair to say, to varying degrees for all of us, our awareness is limited by our training, the practices we employ, the company we keep and the interests we have.

NGOs, ‘not-for-profits’ or ‘for-purpose’ organisations have a particular focus on social impact. Some larger and more organised of these organisations have a ‘business-like’ approach to their work and see the problem to be solved in its complex societal and economic context. These are the organisations most capable of modifying their approach to find opportunities for collaborative approaches to problem solving.

A proposition, then. If we can train NGOs to understand the realities of commerce and companies to see social impact as business opportunity we can accelerate the dual benefits to society of economic and social capital growth.

In particular, NGOs can act as ‘lead generators’ for companies looking for new product and service opportunities, stronger relationships with customers and better ways of doing business.

It sounds more controversial than it is.

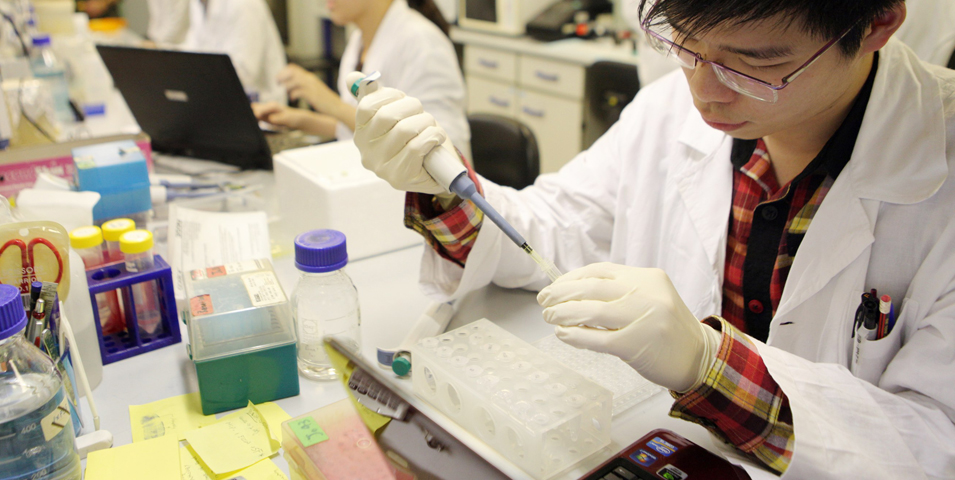

Business has a track record of innovation to solve problems affecting people – from more comfortable beds and healthier food to MRI scanners in major hospitals. But, with legions of employees specialising in skills to deliver an existing suite of services or products (or incrementally build on them), business is unlikely to regularly find new, transformative opportunities. The R&D department is limited not only by budget, but horizon and the awareness of staff.

Enter the NGO. Shared value provides a model for identification and capitalisation on opportunities with social impact – new products, services, processes or relationships. Perhaps facilitated access – via collaboration – to a new market.

The best NGOs are highly adaptive and innovative – they have to be, to survive competition for an ever elusive dollar usually sourced from the common or government purse. It’s a strong place from which to consider shared value and cross sector partnerships with businesses looking for growth or inefficiency but stuck in the frame to see outside.

This article first appeared on Shared Value Project website.