Discussion on the Indigenous Voice to Parliament is dominating our headlines.

And for good reason. If the referendum is successful, the Voice would be a watershed in granting First Nations people a say on the policies and laws that impact them. How? By constitutionally enshrining an independent First Nations advisory body to Parliament.

With the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians only widening on issues such as incarceration, suicide and out-of-home care, an Indigenous-led solution to many of the problems wrought by colonisation is vital – and long-overdue.

Yet amid the media frenzy, false claims are circulating, with fear at the forefront of this momentous moment in Australian history. A moment that – if lost – is unlikely to occur again in our lifetime.

So, how do we separate fact from fiction? How do we drown out the noise and hone in on the message at the heart of the Voice?

It starts with dispelling myths and equipping ourselves with facts. It starts with understanding the rigorous six-year consultation process that produced the Voice – the largest of its kind in Australian history.

But first, why do we need the Voice?

Today, Indigenous Australians stand swimming pools behind their non-Indigenous counterparts on key health, education and economic measures. These gaps stem from the detrimental impacts of colonisation, dispossession and harmful government policies.

The government has implemented various programs to close these gaps since 2008. But many of these targets are not being met. And on some measures, things are actually getting worse.

Why? Well, research shows that to improve peoples’ lives, they first need a say in them. For Indigenous people, self-determination is recognised as crucial to improving health and wellbeing outcomes.

Already, we have small-scale examples of this in Indigenous Australian communities. Take the Northern Territory Well Women’s Program for instance. Based in Yuendumu, a ‘dry’ community of approximately 1,000, mostly Warlpiri people, 290 kilometres north west of Alice Springs, this program emphasises community participation with First Nations women to raise their cervical screening rates.

The program has been effective, achieving a high cervical screening rate (61%) of Indigenous women; a rate that’s comparable to Australia’s average of 62%. Leaders of the program attribute its success to the Aboriginal Health Workers and women feeling a sense of ownership of the program.

Another case study that showcases the positive impact of engaging Indigenous Australians in health services is the Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service in Western Australia. This project has decreased psychiatric admissions of First Nations people to the Geraldton Regional Hospital by 58%. Additionally, the Townsville Aboriginal and Islander Health Service’s Mums and Babies Project has reduced pre-natal deaths from 56.8 per 1,000 to 18 per 1,000.

The evidence is there: when First Nations people drive the solutions to health challenges in their communities, their health outcomes improve.

Even more, there is a clear link between constitutional recognition and improved health outcomes, with successful examples from Canada, Norway, New Zealand and the United States, who all have established models for constitutional and treaty recognition.

Yet in Australia, First Nations people have been excluded from the decision-making process – and the Constitution. In fact, it wasn’t until 2020 – 12 years after the Close the Gap targets were set – that the Australian Government signed an agreement to engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in these conversations.

Our attempts to remedy the wrongs of the past and improve the livelihoods of Indigenous Australians have fallen short. And this is why the Voice is needed.

Acting as an advisory body to Parliament on issues pertaining to Indigenous Australians, the Voice is an opportunity to ensure First Nations people are part of the solutions. It’s a chance to let evidence guide change, and to make a meaningful commitment to improving the lives of Indigenous Australians by letting their ideas be heard.

Six years in the making: the journey to the Voice

The Voice didn’t happen overnight. Momentum for First Nations decision-making to be enshrined constitutionally began in late 2016.

A series of regional dialogue events were held across Australia, as part of a national consultation process on how to best recognise First Nations people in the Constitution.

Of a population of approximately 600,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 1,200 Indigenous delegates met across 13 dialogue events.

Delegates were freely chosen by their communities or representative organisations, with 60 per cent of places at the dialogues reserved for Traditional Owner groups, 20 per cent for community organisations and 20 percent for key individuals.

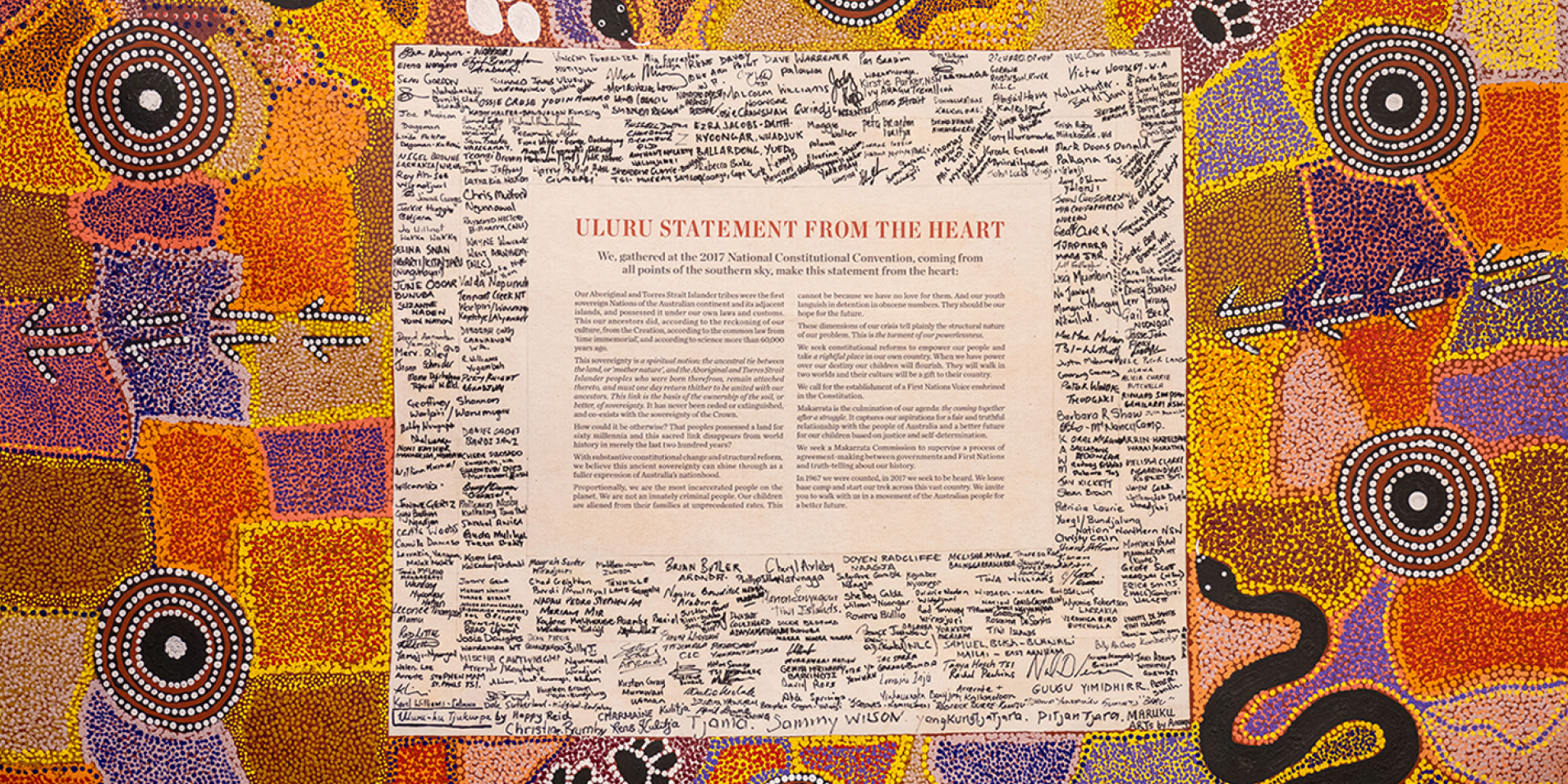

The outcomes from these dialogue events were then reported to the First Nations National Constitutional Convention in May 2017, which ran over four days, and resulted in the Uluru Statement from the Heart – a document that calls for three priorities: a Voice, a Treaty and Truth.

These efforts were mirrored by a broader public consultation process to evaluate attitudes towards creating an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

This online consultation period spanned five months; the different reform options were talked about nearly three million times. 5,300 individuals participated in online and telephone surveys, while 1,111 people made a public submission. The findings? The majority (77 per cent) of respondents supported the Voice.

So, contrary to the false claim that the Uluru Statement from the Heart — which led to the Voice — was written by only 250 Indigenous people, the Voice is the culmination of six years of Indigenous-led dialogues, reports, broader consultation and research.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart is the largest First Nations co-design process in Australian history, which is an achievement, in its own right.

While the Voice would be significant, it wouldn’t be the first advisory group

Already, the Australian Government has 108 committees and groups that provide advice on specific issues. In this way, the Voice wouldn’t be new.

Just like these advisory bodies, the Voice would only have the power to provide advice to the government. No laws can be made by the Voice. And there is no veto power to overturn decisions.

However, what would be different is that the Voice would be written in our Constitution. For it to be removed, another referendum would have to occur.

The logic behind this is to grant First Nations people stable and meaningful change; to ensure Indigenous Australians have a structural guarantee that their voices will be heard. This is especially important since Indigenous government bodies have a history of being formed and then repeatedly disbanded:

- The National Aboriginal Consultative Committee (NACC) was created in ‘73, and then disbanded in ‘77.

- The National Aboriginal Conference (NAC) was established in ‘77, and then disbanded in ‘86.

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was established in ‘89, and then disbanded in ‘04 by a collection of subject-specific committees.

This pattern of previous bodies failing was a failure of governments to listen, accept criticism and continue adequate funding. Having a constitutionally enshrined Voice would thus be a step forward in preventing this cycle from repeating itself.

With a system that is failing Indigenous Australians, something must change. It’s time to move away from our ineffective status quo and towards well-informed policies. It’s time to address systemic inequalities. And it’s time to listen to the evidence, which means, listening to the voices of Indigenous Australians.

Are we ready to listen?

Most Indigenous Australians support a Voice to Parliament. In fact, one of the largest and most representative samples to date, shows that 83% of First Nations people support a Voice.

And yet, alarmingly, this same research found that non-Indigenous Australians are struggling to trust this, with only 40% of non-Indigenous Australians believing a majority of First Nations people support the Voice.

This disparity between what Indigenous Australians say and what non-Indigenous Australians believe was supported by focus groups on non-Indigenous Australians’ attitudes towards the Voice.

So, although a plurality of perspectives exist within First Nations communities, we have evidence that an overwhelming majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are calling for change.

While the reasons for the Voice are clear, our collective voice is not.

On 14 October, we will come together to cast our votes in the referendum and make our voice – as a nation – known.

Will it be a statement of hope, unity, recognition and change, towards a more equal Australia? Or will it be a call for the status quo?

Will we exude the ability to understand – not just the question at hand – but why it’s being asked of us in the first place?

Will we walk with Indigenous Australians for a fairer future? Or will we let fear prevail?

When someone uses their voice, the least we can do is listen.

So, will we?

Image: Uluru Statement from the Heart.