How does public hospital funding work today?

As it stands, the current model for public health care and hospital funding is broken. The current plan for 2020 retains activity based funding (ABF) and National Efficient Price (NEP) as the basis of the $21.1 billion hospital fund distribution to the states and territories.

ABF applies a funding methodology based on the level of hospital activity and the complexity of cases (case-mix) using the NEP to calculate the cost of these. Hospitals are paid on the basis of the number of cases, adjusted by case type. However, the current model – essentially creating funding based on beds and occupancy – is not coping with the changing demographics and the health of Australians.

Jane Hall and Rosalie Viney describe this on The Conversation.

Under the activity-based funding system, prices per unit of activity have stabilised. But total expenditure equals unit price by volume, so while price is steady, increases in hospital admissions (and case severity) are driving growth in total expenditure.

It is clear both from theory and international experience that activity-based funding addresses the first (admissions) but not the second (volume). Recent data shows the number of admissions to public hospitals increasing by 3.5% a year over the past five years, with the rate increasing more in most recent years.

With chronic disease rising rapidly and an increasing ageing population, to model a funding scheme where the demand far outweighs the supply is fraught with error. As a model for hospital funding, it is out of date.

How does this work in the real world?

Let’s take Northern Health as an example. Northern receives substantial government funding (around $36 million monthly from ABF). However, it manages one of the most diverse and fastest growing populations. They are the major provider of acute, sub-acute and ambulatory specialist services for the Northern Health catchment area that includes three of the state’s six highest growth areas. The population is projected to increase from 350,000 people in 2016 to more than 570,000 in 2031. A large percentage of this population is made up of migrant, refugee and multicultural residents and very high rates of socioeconomic disadvantaged residents.

A lot of work is being done in this area and a lot of research-driven programs are conducted to support the management of chronic diseases and patient education. In simple terms, if the same number of beds exists for a nearly doubling population, the focus should be on lowering the number of admissions, providing higher quality care planning and ensuring the patient is equipped to better manage their health and reduce the risk of readmission.

How does change occur?

Essentially, change in hospital care planning revolves around a better understanding and usage of data. Unwarranted variation (or geographic variation) in health care service delivery refers to differences that cannot be explained by illness, medical needs, or evidence-based medicine.

This can be rectified with a comprehensive data strategy. Initiatives addressing this have started to emerge in the UK.

Tim Briggs leads a programme called Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT). He thinks it could ultimately save the English NHS £1.4bn (€1.5bn; $1.8bn) a year by helping trust managers and hospital teams to use the masses of data they gather — on everything from procurement to types of treatment used and length of stay — to improve care and eliminate waste.

If we continue to fund based on volume, inroads into improving the health of our population will never be achieved. If the funding model is flipped to support quality of care and patient outcomes, we will begin to make strides into reversing the current trends. One bed that isn’t occupied with a returning patient is a bed that can be used to treat another patient.

An aspect of this approach is also described in the above article.

Improving health sector productivity will require a more system-oriented approach, with the concept of a nationally efficient price extended to more health services including those provided in the community. An “episode of care” extends beyond the hospital walls and includes GPs, specialists, pathology, pharmacy and so on.

How does this approach work?

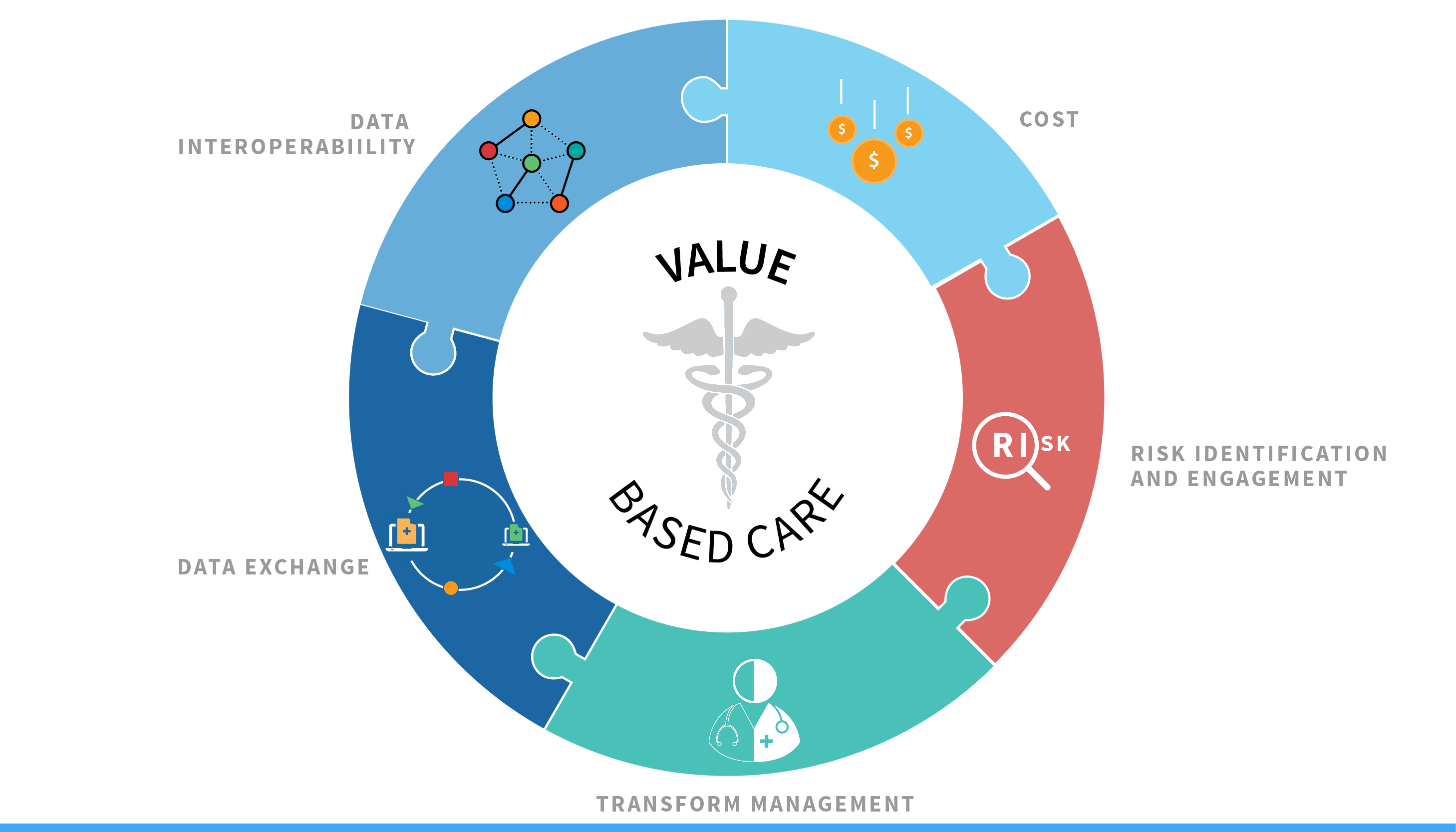

This type of approach is known as value-based hospital funding, and is being advocated for by associations like the Australian Health and Hospitals Association (AHHA). This includes redirecting money into prevention and better primary care, and incentivising better outcomes for patients.

While the government may lag behind in its thinking, value-based modelling is being conducted elsewhere. In 2013, Sahlgrenska University Hospital’s CEO, Dr. Barbro Fridén, determined that value-based health care should be one of the hospital’s three areas of strategic focus. In its work with the senior-management team at Sahlgrenska, BCG used a version of the self-assessment tool portrayed below. The outcome of this assessment process prompted the decision to start with four pilot initiatives, each focusing on a particular disease or procedure: bipolar disease, prostate cancer, hip arthroplasty, and pediatric cardiac surgery.

CEO of AHHA, Alison Verhoeven has stated “while refinement of the existing funding model is required, there should also be a focus on models that include rewards for continuous improvement that are applied at the point of service provision. This approach, in combination with transparent benchmarking and reporting and clinician engagement in the improvement process, can achieve the dual goals of improved efficiency and better patient outcomes”.

- Assess organisational readiness. Carefully assess operations against a comprehensive set of criteria based on best practices established by leading value-based organisations.

- Define the outcomes that matter to key patient groups. Set up multidisciplinary teams, including patients, to define the key metric outcomes that matter for those groups.

- Allocate costs per patient. Discuss how each step in the clinical pathway contributes both to outcomes and to costs.

- Implement quick wins. Identify areas that can be immediately improved.

- Enhance service function productivity. As suggestions accumulate through pilot programs focussing on key patient groups, consider how functional units such as radiology and ICU may need to change their processes, roles, and performance metrics to better satisfy the needs of high-value patient care.

- Institutionalise the value-based approach. Develop recommendations for how the continuous tracking of outcomes and costs per patient can be integrated into the day-to-day management of the organisation. Consider adjustment in organisational structure, roles and responsibilities, ensure that IT systems facilitate this work and enable the clinical teams.

How do we apply this approach?

How do we apply this approach?

How would this model be applied to an organisation like Northern Health even when the current hospital funding model doesn’t support the approach? Initiatives may include patient consultation platforms, follow up or monitored care plans for each individual, or education pathways for citizens. With clinical evidence and evaluation underpinning initiatives, benefits can be gleamed by both patient and organisation.

Broadly, through a combination of impact modelling and digital / data strategy, any organisation in the health space can make steps towards value-based care. It requires support from the top down, but awareness and implementation of initiatives can be generated by every employee.

A move to value-based care will have economic benefits even within the current funding models. The challenge is not in filling beds; it’s in filling beds with the right patients and ensuring their chances of readmission are as low as possible. It’s also ensuring that staff, systems and processes are all properly working towards improving health outcomes through consistency, accuracy and efficiency.

An initial benefit should include reducing unwarranted variation and better outcomes (as measured by patient-reported outcome measures). Improving patient care also increases staff morale and retention. More organisations taking this approach will also lead to greater research opportunities and outcomes.

There are huge opportunities available to health care organisations of all types to start implementing these approaches to their care provision. While Australia may be playing catch up in the space, the shift is happening and the more proactive an organisation is, the greater impact they can produce.